How much input do you need to speak English fluently?

How much information do you need?

Few people realize that learning a language fluently is a much more memory-intensive task than, say, learning organic chemistry or the history of Europe at an expert level.

Let’s consider the number of facts you need to know to produce correct English sentences with ease. Certainly you must know the meanings and pronunciations of something like 10,000 words and phrases — the contents of a medium-sized dictionary. But this is only half the picture. The other half are thousands upon thousands of little facts which tell you when to use different words and how to combine them with other words:

-

We say “I walk”, but not “

he walk”; “he says” but not “he mays”; “Is she young?”, but not “Looks she young?”; “He did it”, but not “Hedidn’t it”; “She looked beautiful”, but not “She dressed beautiful”. -

We say “Mary likes cheese very much”, but not “

Mary very much likes cheese” or “Mary likes cheese much”; “He might have eaten the cake”, not “He could eat the cake” or “He has might eaten the cake”; “What did he eat?”, not “What he ate?” or “He ate what?”. - We do an exercise, but make a mistake; make a phone call, but have a conversation; do a job, but take a break; take a step, but make a jump.

-

You can have a bad/terrible headache, but not a

strong/heavy headache; you can get great/enormous satisfaction, but notbig satisfaction; you can be a heavy smoker, but not ahard/strong smoker; you can have a heated debate, but not aburning debate; you can have a fast car, but not afast look; you can clean your teeth, but you cannotclean the dishes. - We talk about something, comment on something and discuss something; succeed in something, but fail at something; ask a question of somebody, but have a question for somebody; accuse somebody of something, but blame somebody for something; answer an e-mail, but reply to an e-mail.

-

You can give an opinion, but not

an advice; buy a cake, but nota bread; move a table, but nota furniture; share a fact, but notan information. -

You can ask somebody to do something, but not

suggest somebody to do something; you can tell somebody something, but notexplain somebody something; we encourage somebody to do something, but discourage somebody from doing something; we tell/want/get/allow somebody to go, but let/make/see/hear somebody go.

A book like Michael Swan’s Practical English Usage has 600 pages of facts like these. And I wish I could tell you that they are unnecessary – that you can just ignore them – but the fact is, I obey virtually all of these rules when I speak or write in English, and so does anyone who is fluent.

If knowing a language requires so much knowledge, then how come everyone can speak at least one language fluently? We are not all Einsteins. There are many native English speakers who are not very skilled at acquiring knowledge, yet all of them successfully use the dialect of English that is spoken in their community (whether it is standard English or the Black English Vernacular).

The reason why we can memorize a huge database of language facts is the same reason why we can recognize faces. Consider how much information is required to recognize that Bill is really Bill: the dimensions of the head, the colors, shapes, relative sizes, and positions of the eyes, nose, eyebrows, lips, teeth, ears, chin, cheeks, forehead, hairline, hair, wrinkles, spots and facial hair. If I were to write down a precise description of just one face, imagine how many sheets of paper that would take, and how hard it would be to memorize. Yet all of us (even people with a poor memory) can recognize thousands of faces and it takes only a blink of an eye in each case.

We can do this because we don’t have to memorize people’s facial features like we would memorize history facts. Our brain has a special module which can instantly grab all the data as we look at a face. Then, when we look at a face, this module can answer the question “Do I know this face?”. It all happens effortlessly and subconsciously. We never have to think “Um, the convex shape of this person’s nose, the distance between the eyes, and the asymmetrical upper lip match my friend Peter”.

Just as everyone (smart or not) has a face recognition module, everyone has a language module. This module stores facts about word meaning, word usage, grammatical structures, pronunciation, etc., so you don’t have to memorize them like you would memorize history facts. While the face recognition module lets you answer the question “Do I know this face?”, the job of the language module is to produce correct sentences based on what it has learned about language.

How does the language module get its facts about language? Unfortunately, it takes more than a quick look. Long lists of rules (like the one above) won’t help either — the language module evolved long before there were grammar books, so it doesn’t understand grammar rules. The module gets its information from example sentences. As you read and listen to correct sentences in a language, it builds, piece by piece, a database of facts about that language.

How much input do you need?

All right, so the language module in your brain needs correct sentences. But how many sentences do you actually need to become fluent in a language?

First of all, the question is a bit misleading, because there isn’t a single answer for all situations. The number of sentences you need will depend on many factors:

- the difficulty of the sentences (e.g. if you get too easy or too difficult sentences, you won’t learn much)

- the style of the sentences (if you read too much literary language, it will not help you speak)

- your pace (if you get more sentences per day, you need fewer sentences in total, because you forget less information)

- how you get the sentences and how much attention you pay to them (when reading, it is possible to analyze each sentence much more carefully, so you can get more information out of each sentence, but you also read more slowly)

- your innate skills (some people need more input before they can speak, others “get it” very quickly)

- how close your first language is to the language you are learning (a speaker of Dutch needs much less input to learn English than a speaker of Japanese)

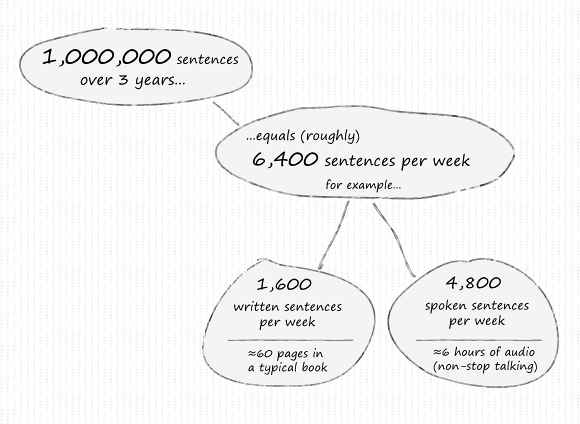

How much input did I get? It took me about 3 years to get from basic English skills to fluency. During those 3 years, I was exposed to about 1,000,000 English sentences (not necessarily different sentences). About 400,000 of these were written sentences (books, SRS reviews, dictionaries, classroom reading); 600,000 were spoken sentences (TV, recordings, listening to teachers, listening to my American cousin, classroom listening).

Note that these are very rough estimates. The actual number of sentences that I got during that 3-year period may well have been 700,000 or 1,500,000.

“Holy moly!”

I know. One million is a big number. But when you break it down, it looks far less scary:

So if you want to follow in my footsteps, you’ll have to get about 60 pages of written English and 6 hours of spoken English per week — for three years. (I am assuming you already have some basic English skills that enable you to understand this article. If you are a total beginner, you will have to get to that level first.) If you think 60 pages and 6 hours is a lot, consider the following points:

- Using an English-English dictionary with example sentences and SRS reviews take care of perhaps 15 pages of written English per week. This leaves 45 pages per week for traditional reading (websites, books).

- Reading 45 pages per week may seem scary when you are just beginning to read in English. But I promise you — you will be devouring English texts in no time!

- Remember that things like listening to your teacher, having conversations in English, watching videos on YouTube, watching House M.D., playing Mass Effect, etc. all count as “listening time”. (Note that to get 6 hours’ worth of “pure” spoken English – the amount you would get from listening to a 6-hour interview – you may need to play a videogame for 30 hours, as most of the time in a typical game is spent doing other things, like shooting zombies.)